How improving product safety can accidentally create riskier behavior — and what smart product makers do about it

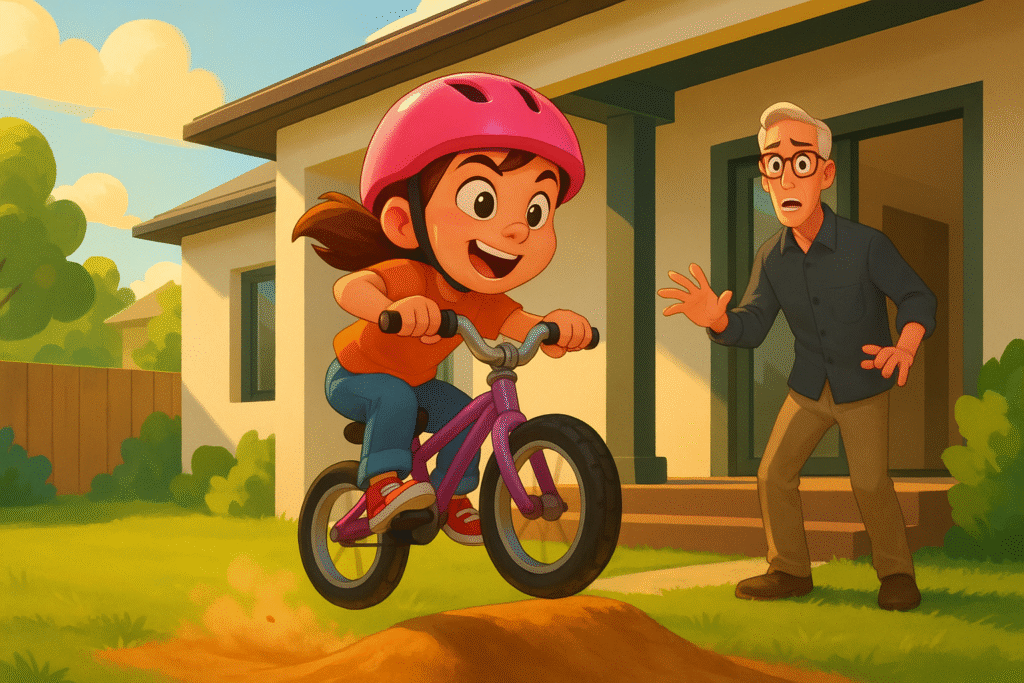

I remember when my youngest daughter got her first bike helmet.

Suddenly, she’s attempting stuff that would have terrified her when she was bare-headed.

Welcome to the Peltzman Effect in action.

Named after economist Sam Peltzman, this cognitive bias reveals something pretty counterintuitive: when we make things safer, people start to take dumber risks.

Drivers go faster when they get anti-lock brakes.

Rock climbers attempt harder routes with better gear.

Kids get bolder with protective equipment.

The safety improvement gets offset (or more) by behavioral compensation.

I see this constantly in product development.

A client creates an “idiot-proof” version of their software — and suddenly users attempt much more complex workflows without reading instructions.

Another builds extensive safety features into their hardware — and customers start using it in environments it was never meant for.

In I Need That, I wrote about how safety needs are fundamental drivers of purchasing decisions.

But then, here’s what a lot of product makers overlook: improving safety can paradoxically increase unsafe usage patterns.

Ring doorbells and others like them made home security so much more accessible — but some users became obsessively vigilant, checking notifications constantly and confronting semi-suspicious neighbors more aggressively.

Ride-sharing apps like Uber and Lyft made getting home safer than flagging down random cabs — but also enabled some people to venture into unfamiliar areas they’d previously avoided.

It’s not that safety features are bad.

It’s that human psychology is really complicated.

Our ancient brain recalibrates risk on the fly. When one danger decreases, we unconsciously permission ourselves to take risks elsewhere.

Product Payoff: Volvo discovered this firsthand when they introduced advanced safety systems. Some drivers began following more closely and braking later, trusting their collision avoidance technology. Volvo responded by designing their safety messaging around maintaining good driving habits alongside technological protection, rather than positioning their cars as invincible.

The smarter, safer approach: When YOU add safety features, educate users about maintaining safe practices rather than only highlighting protection.

Show the boundaries of what your safety improvements can and cannot handle.

Design for the predictably riskier behavior your improvements might encourage.

Remind yourself: people buy safety for permission to feel more confident in challenging situations.

What unexpected behaviors have you noticed when customers feel “safer” with your product?

Hit that reply arrow and share your Peltzman Effect stories — the times improved safety led to surprising risk-taking.

Or safely reach out to my team of product marketing strategists at Graphos Product.